“I’m letting myself go … but it’s just for today!” This is a very common phrase I hear when I go out to eat. Heck, it’s a phrase I often use, myself, whenever I go to a fancy restaurant or just happen to be eating something extremely delicious with a bunch of friends. This phrase becomes even more common when it involves someone who is on a diet and decides to give him/herself a day off the diet in order to indulge in whatever decadent food is there. This idea of having a “cheat day” or “cheat meal” is quite common in a lot of material about dieting; it understands how hard it is for people to stay disciplined to a limited number of calories for an extended period of time.

Cheat days

I find the idea of the cheat day quite fascinating because at the heart of it, the cheat day recognizes just how much we are prone to give into temptation. On one hand, this term has been coined with the word “cheat,” meaning that allowing oneself a day to indulge every week is cheating and that constantly sticking to a low calorie diet all the time would be even better if done without cheating. On the other hand, the whole point of the cheat day is to say that it’s okay to have a day to eat more decadently without feeling guilty because otherwise, one might be tempted to quit the diet, or worse, go on a complete binge of decadent food.

Basically, cheat days are a “bend but don’t break” approach, somewhat similar to approaches that are often suggested for other tasks that require discipline such as taking planned breaks while working or having designated off-days when working out. What’s different in these two cases, however, is that the break from the activity actually has additional benefits. A break from can help refresh your mind and give new perspective when returning to the work, and days off from working out gives your body time to rebuild muscle. Based on my understanding and research (basically some Googling) of cheat days, the only “benefit” is reduced temptation to stop dieting/go on a binge eating rampage. But is this really how we should approach the occasional indulgence of food? “It’s okay to let go every once in a while because it’s better than really letting go and completely giving up on a diet.”

Why all this fuss about “cheat days?”

Recently, there were two blog posts written on opposite ends of the same topic, unhealthy approaches to eating. On one hand, there is over-eating, gluttonous eating, and on the other hand, there is under-eating, which is often associated with having an eating disorder. (As a side note, I recognize that I’m oversimplifying things quite a bit. Over-eating and under-eating do sometimes go hand-in-hand, and eating disorders are extremely complicated. Unfortunately, there’s not enough time in this post to delve into details nor am I really one to speak much on this.) As discussed in both blog posts, neither of these is simply to be identified simply by looking at a person’s weight. While weight can be an indication of habitual over-eating or under-eating, these unhealthy approaches to eating are often linked to other issues of the heart, such as body image or escaping stress just to name a few.

What I dislike about the current way that our culture approaches “cheat days” is that it feeds into many of the issues of the heart that come with gluttonous eating and eating disorders. “It’s okay to indulge once a week because you’ve dieted so well the other six days that you’ll still be net minus 200 calories for the week and on your way to a better body.” “It’s okay to eat something fatty today; you deserve something tasty after all those nasty kale/quinoa/beet/insert other healthy veggie juice drinks.” (For the record, I have nothing against kale/quinoa/beet/other healthy veggies or juice drinks) Cheat days don’t even begin to address the heart related issues that come with unhealthy eating; rather they exist only in the framework that has already bought into the idea that the heart related issues will be solved through eating or not eating. More explicitly, the cheat days mentality has already accepted that a person who is struggling with under-eating because of a body image issue will only be happy once that body image goal is met. Similarly, the cheat days has ceded that a person who is struggling with binge eating because of stress he/she will only feel better by over-eating. The next step in both cases is just to try to control the eating amount. Only the symptom is addressed, not the root.

There are a few natural follow-up concerns with only addressing the symptom of excessive over-eating or under-eating. How much can I go over my normal amount on a cheat day? If I can just grit it out and not cheat at all, wouldn’t that be better? What happens if the symptom is fixed, but the underlying issue persists, won’t it all just collapse?

This makes sense, but why are you trying to ruin a good thing? Lots of people do this and are losing weight and getting healthier. Just let people eat how they want to eat.

For the record, I don’t find anything wrong with the simple practice of having certain meals where one would eat more or more decadently than he or she usually does. This does have the practical effect of encouraging people not to binge eat or give up on trying to eat healthy, which is good as well. My main point is that cheat days, as we’ve constructed them, undersell the beauty of food and what food means to us as humans. Instead of appreciating what God has given us in food, we view it merely as a means to please ourselves and get what we desire. Food is meant to be enjoyed as a gift from God and a reminder of our dependence to God. What the cheat days mentality does is place ourselves above food, giving us the power to eat or not eat it as a means to control our body image, stress, and more.

Okay, so you don’t like this construct, but you like the practice. What do you propose instead?

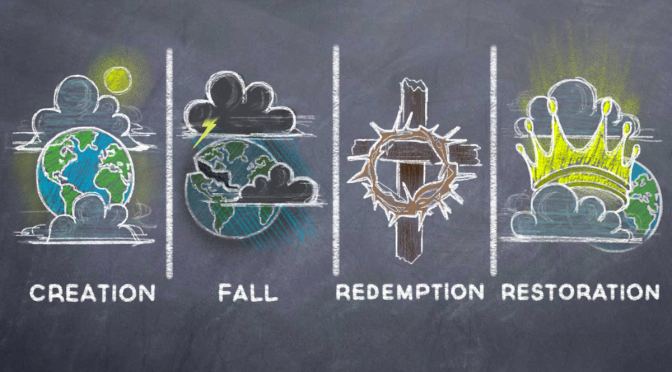

In a Gospel Coalition blog post title “Toward a Theology of Dessert,” (http://thegospelcoalition.org/article/toward-a-theology-of-dessert/) the author proposes that we consider “dessert as feasting.” She introduces an interesting biblical framework for understanding how we eat; there are three primary modes of eating: feasting, fasting, and ordinary. While I’d love to go into more depth about this, for now, let’s just focus on feasting. In the Bible, we see God calling us to feast as a way of celebrating His goodness and provision for us. For example, Leviticus 23 lists out the seven feasts (Passover, Unleavened Bread, First Fruits, Pentecost, Trumpets, Atonement, and Tabernacles) in which the Israelites are to partake. In Revelations, we are told that in the new Jerusalem, we will partake in the “feast of the Lamb.” In the story of the prodigal son, when the son returns, the father kills a fattened lamb to eat and throws a party for his son’s return. In these examples, and more, we see food as a celebration of God and what he has given us.

With this in mind, I believe a more appropriate perspective on cheat days is to consider feasting as the times when we can “let go.” I don’t have a particular definition in mind for what constitutes a feast in our context, but this could include times of eating with friends, celebrating a birthday, housewarming parties, and more. Rather than viewing times we indulge as a cheating from the norm and something simply to be done to prevent further backsliding, feasting tells us that these are normal and celebratory occurrences. After all, it’s not cheating if God wants us feast.

Final Remarks

I feel there’s quite a bit more to say about understanding God’s desire for us to have times of feasting, but perhaps that will come in another post. Having a mindset of feasting retains the positive practical aspects of cheat days, while also providing a better understanding of food’s purposes and limits. I’m not going to pretend that this change in mindset will somehow solve the many of the heart issues that lie beneath unhealthy eating approaches. Those heart issues, ultimately, are not things that will be solved by food, period. What feasting does do, as a mindset, is recognize that ultimately all things point to God, and hopefully in this tiny way, will remind us that the heart issues are ultimately resolved in finding God.