Whenever I introduce myself as someone studying architecture, the question that I get asked a lot is: what kind of buildings do you want to design? Even a google search of the word ‘architecture’ suggests that this is the most important question that anyone in the field of architecture must answer. The search results bear buildings that range from the Florence Chapel to slick contemporary buildings of Zaha Hadid: and in case you can’t find the particular ‘architecture’ you were looking for, you can take up the offer of suggested further searches, whether it be ‘traditional’ or ‘minimalist,’ a ‘house’ or ‘skyscraper,’ But regardless of the diversity in these definitions of architecture, one thing remains constant throughout all the images: that there’s a difference between the everyday buildings that we see and a “work of architecture.”

Now the whole world had one language and a common speech. As people moved eastward, they found a plain in Shinar and settled there. They said to each other, “Come, let’s make bricks and bake them thoroughly.” They used brick instead of stone, and tar for mortar. Then they said, “Come, let us build ourselves a city, with a tower that reaches to the heavens, so that we may make a name for ourselves; otherwise we will be scattered over the face of the whole earth.”

Genesis 11:1 -4

One of the earliest examples of architecture in the Bible is the Tower of Babel. The passage in Genesis 11 tells us that the people of the earth artificially made building materials that would have a structural capacity greater than found materials. This new means of building stirred great ambition and collaboration among the people of earth, in the hope and excitement of a new architectural possibility that could stand as a hallmark of mankind. If there was anything for the future generations to remember this generation by, it would be through this monumental building.

Even though the tools and materials of the trade have changed since the biblical times, this desire has always remained the driving force of architectural development. Whether it be pushing for new materials, construction, form, or ideal, each new generation craves and produces a Babel that would embody the forward-moving geist of its time and people. As a result, the focus of architectural discourse has been the large-scale phenomena—of what is happening to the society at large—and its products landmarks that commentate on these broader shifts occurring in the ‘today’ of a present.

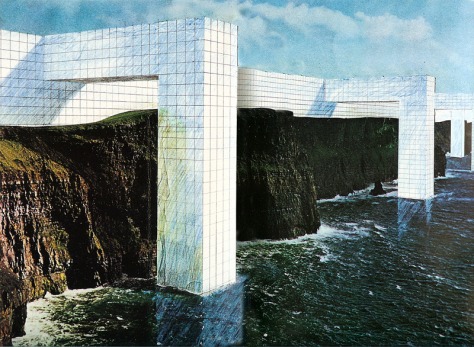

A drawing from Continuous Monument and 12 Ideal Cities (1969-1972)

A drawing from Continuous Monument and 12 Ideal Cities (1969-1972)

The landmark can be theoretical, physical, or both. In some cases, the architect writes manifestos on the social, political, or technological issues he or she finds important or problematic and pairs them with an architectural proposal, represented by visual aids such as diagrams, collages, models, etc. At times, the architectural proposal is architecture as an idea but not necessarily a building. Case in point is the works of Superstudio (1966-1978), a collective from Florence, Italy that did not have a single built project but produced a series of collages showing endless gridded structures that dominate the picture frame and engulf entire cityscapes as a critique to the megastructural developments that act “as a metaphor for the ills of globalization and unchecked proliferation of homogeneous modern architecture.”

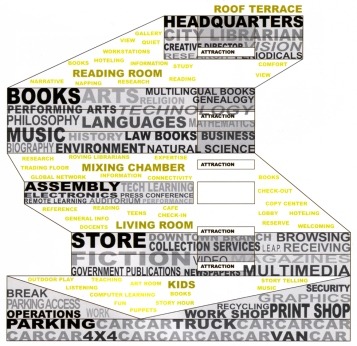

In other cases, an architect’s landmark contribution is a physical construction as Babel was, offering a reinterpretation or a critique of an existing building type and its function. OMA’s Seattle Public Library is a building that is probably familiar to most architecture students of today, with its significance lying in the fact that the book stacks are not stored on floors but become a spiraling ramp hang like an orange peel, with event or sitting areas labeled as “living rooms” or “mixing chambers” filling up the space in between the ramps. Students are shown architectural works like these as exemplary works and are encouraged to create projects that also dare to be different and provocative, not accepting anything as a norm and challenging them to produce an alternative “solution.”

Diagrams and photos of Seattle Public Library by OMA

Diagrams and photos of Seattle Public Library by OMA

From these examples—though we do not explicitly say it—it’s clear that the pervading motto of modern architecture is “big ideas and/or big buildings.” With this motto, the greatness of an architectural work is based on its scale, whether it be the scale of its building or the scale of its impact in the discourse; there is little room for the mundane, the common, and the everyday.

Tower of Babel by Pieter Bruegel

Even though it was painted centuries ago, Pieter Bruegel’s Tower of Babel is a painting representative of this tendency of ours and the impact it has on the existing city and its people. In the painting, the tower dwarfs its neighbors, the two- or three-story buildings with pitched roofs; the size of the new building comparable to the entirety of the existing city surrounding it. What strikes me about this painting is that it lays bare the intention of the building and the designer to create physical and social disparity both within the construction process and in the larger society. The building creates an enclave, a separate city in which its inhabitants can likely live and carry out their daily functions without having to step outside its walls (imagine how many CVS’ and Stop and Shop’s could fit into that thing).

Oftentimes the product of the building takes up so much of our attention that the interpersonal consequences the process brings (both pre- and post- completion) are left out of the picture. Even though what we make is a building, the decisions that lead up to its building is a series of choices on who we work for. The clients we choose to work with influences where we work, what type of building gets designed and built, and who we work with (contractors, consultants) in order to complete the project. As a result, the physical architecture is heavily dependent on the partnerships we choose to develop.

I think one of the biggest mistakes that any student or professional in the field can make is to think that design only occurs in the building, when in reality the design begins much before in the shaping of this social infrastructure: in the moment we choose to shake our hands and work for one person or group rather than another. Architects oftentimes try their hardest to divorce architecture from the socioeconomic and even political implications or role it plays. For instance, Léon Krier published a book on Albert Speer, Hitler’s architect, asking the question: “Can a war criminal be a great artist?” Yale School of Architecture’s previous dean, Robert A.M. Stern, who wrote the preface to the book, had been quoted by a classmate to having said that one must be able to appreciate architecture for its architecture (not word for word and don’t know how reliable this is). For both men, the value in an architectural work should not be dismissed by the fact that they had been “tainted” by politics, suggesting that we should be able to look beyond the political associations of an architect’s work and evaluate its architectural accomplishment solely within the built work.

But the reality is, projects such as Albert Speer’s—perhaps especially those such as his—stand in history precisely because of the power of their clients. Because architects do not and cannot fund their own buildings, the capacity of a built project to reach a certain size and achieve a certain quality inevitably depends on this power, whether that power be political or financial. If there was no Hitler, there would have been no Cathedral of Light and other neoclassical works by Speer that would have been left for us posterity to reflect upon. And so architects stand in defense of the “architecture for architecture’s sake” philosophy; architecture must and does live on, and it doesn’t matter which lifeline we choose to support it on. This statement could have been intended as a message of empowerment but I think it actually works in the reverse and exposes it for the frailty that it is. As long as the definition of architecture or “great” architecture remains fixated on grand, interesting, or new forms, architects will always be chained to a client who is able to provide the means of doing so. Ironically, the pursuit of architecture for architecture’s sake becomes inseparable from the pursuit of a powerful client.

But he said to me, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness.” Therefore I will boast all the more gladly about my weaknesses, so that Christ’s power may rest on me. 10 That is why, for Christ’s sake, I delight in weaknesses, in insults, in hardships, in persecutions, in difficulties. For when I am weak, then I am strong.

2 Corinthians 12:9-11

So “who do we build for?” becomes a question that is just as if not more important than the question of “what do we build?”On one hand, the perspective mentioned above is an acceptance of the fact that architecture is perpetually weak, utterly helpless beneath its mask of grandeur. But what if we understood and sought great architecture as something else? The passage in 2 Corinthians 12 tells us that it is when we are weakest that we are made strong. What if the most powerful architecture happens in not the acceptance but the rejection of the powerful as our partner in the construction of our buildings? This is a scary question for a lot of architects, especially when money is in the picture. After all, architecture firms are private practices that stay afloat mostly through the margin of profit they gain from commissions. The more and expensive the commissions are, the better they are for the financial health of the company. However, at times I wonder whether this model is truly one of health or gluttony, inherently necessary or brought forth due to a firm’s desire to take on projects and to become better known in doing so. I wonder whether firms see themselves as the small houses or the Babelian tower but at the same time sadly know that a lot envision themselves being the latter.

One of the teachers of the law came and heard them debating. Noticing that Jesus had given them a good answer, he asked him, “Of all the commandments, which is the most important?” “The most important one,” answered Jesus, “is this: ‘Hear, O Israel: The Lord our God, the Lord is one. Love the Lord your God with all your heart and with all your soul and with all your mind and with all your strength.’ The second is this: ‘Love your neighbor as yourself.’ There is no commandment greater than these.”

Mark 12: 28-31

I bring up this passage from Mark 12 because it not only reminds me of the importance of asking the question of “who” but also reminds me of the answer that God calls me to give. In the passage, Jesus uses the word ‘neighbor’ rather than the generic word of the ‘other’ to describe those whom we should love and serve. In the past, the passage had a broad, watery application in my life where I understood the word ‘neighbor’ to mean anyone that I encounter in this word and Jesus’ message as a call to “be nice to everyone.” But reading it recently has led me to understand that the word ‘neighbor’ has greater specificity than that. First and foremost, ‘neighbor’ implies a location. Being a neighbor and having a neighbor means that I am a part of a neighborhood in which I am a neighbor to someone and someone is a neighbor to me. It means that there is a physical place that I am a part of, to which I belong and identify with. And even though our modern ways of living has long since transitioned from the communal lifestyle of villages to autonomous dwellings compacted in bigger and taller buildings, I think Jesus calls us to anchor ourselves once more to a place, if not physically at least devotionally.

The Lord had said to Abram, “Go from your country, your people and your father’s household to the land I will show you.

Genesis 12:1

This goes back to even the earliest parts of the Bible, from when God calls Abraham out of his nation to the land of Canaan, with the narrative of the people of Israel inextricably tied to the displacement from and return to this promised land, from a scattered to a collective whole. And so the question that has been lingering in my mind is: where is this land that God is calling me to return to? Who is the people of God that He is calling me back to be a part of or, perhaps even to lead?

Last morning I was talking with my father who had spent decades in the states before he returned to his small hometown in Korea to work with those there and to serve his parents. I asked him, “did you know you’d be going back one day?” to which he answered that he knew he wanted to, but didn’t know until the moment the opportunity came that this prayer would be realized. The years in the states was a time in which God tested and disciplined him, after which he was led back to the land of his forefathers; years in which he had made a name and place for himself there but always knew that he belonged elsewhere. Although some might read his resume and imagine him being someplace else, he knows that there is no other place to be than where he is now with those he is with.

Maybe right now is just the start of my own forty years in the desert, where I wander through trials and tribulations. At times, I might even yearn to go back to my own Egypt, my own Babel, rather than to yearn for a homeland that God calls me to be. But I hope that I despite these times to never give up that yearning for the place where I can finally arrive and remain: to be in and a part of a place where I’ve not only helped to build and fix some of its buildings but where I’ve seen it grow and change over time with its people—where I can testify to God that, indeed, I have found, loved, and remained with my neighbors with all my heart and my soul.